“You’re travelling through another dimension, a dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind; a journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination. That’s the signpost up ahead—your next stop, the Twilight Zone.” –Rod Serling’s opening narration

Submitted for your approval, The Twilight Zone, a science-fiction/fantasy/horror anthology series created by Rod Serling that first aired in 1959—and remains one of the most influential television shows ever made. Over the course of five seasons and 156 episodes, Serling—who was also the show’s executive producer and head writer—presented viewers with a brush with the uncanny. A man looks out of an airplane window and sees a gremlin on the wing. Five people are trapped in a room with no memory of how they got there. A woman goes shopping and ends up on the ninth floor of a department store which only has eight.

Serling and his writers, including the likes of Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont and Ray Bradbury, wrote searching, often searing social commentary and snuck it past censors under the guise of sci-fi and fantasy. Most episodes ended with a moral and the main character meeting a suitable (or suitably ironic) fate.

Parodied and referenced by everything from The Simpsons to Blazing Saddles, The Twilight Zone has also spawned a film, a radio show, a pinball game, action figures and a Disney theme park ride. And its distinctive theme (nene-nene nene-nene), composed by Marius Constant, has become shorthand for bizarre happenings.

The show has been revived thrice: first in 1985, as an uneven, but frequently worthy successor to the original series; in 2002, to lesser effect; and now in 2019 as a series hosted by Jordan Peele. ‘The Comedian’, the first episode of Peele’s series, is disquieting, thought-provoking and available for free on YouTube. I highly recommend it.

Every Twilight Zone fan has a list of favourite episodes. These are mine.

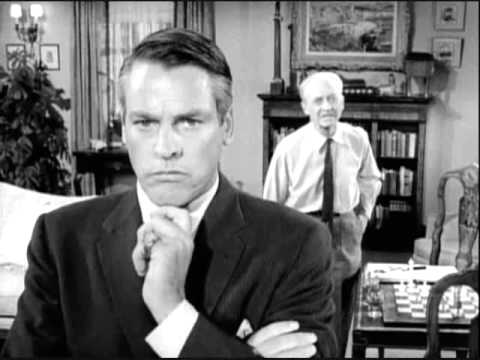

‘Long Live Walter Jameson’, season 1, episode 24, written by Charles Beaumont

History professor Walter Jameson (Kevin McCarthy) astonishes his students and colleagues alike with lectures so vivid, it almost seems as if he’s lived through the periods he describes. For good reason: he has. Long ago, Walter’s fear of death led to a rash decision that cost him his family, his friends and the joys of a mortal life; thousands of years later he still dreads the grave and cannot face it. Beaumont confronts us with the chilling prospect that a man might achieve great age and experience, yet still be without wisdom. McCarthy’s eyes are weary but selfish: Walter’s years have given him a calloused heart and beneath his smile lurks a spiritual abyss. A haunting episode and my favourite of the entire series.

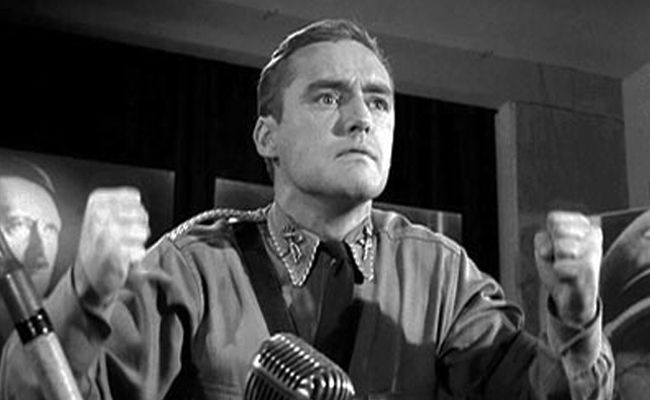

‘He’s Alive’, season 4, episode 4, written by Rod Serling

Dennis Hopper stars as Peter Vollmer, a neo-Nazi pontificating on street corners to a crowd more likely to beat him up than to listen. He is, according to Serling’s narration, “a sparse little man who feeds off his own self-delusions and finds himself perpetually hungry for want of greatness in his diet”. When his closest friend—paradoxically, a Jewish Holocaust survivor—accuses him of peddling hate, Vollmer insists that he is simply stating his point of view. Then a mysterious advisor appears out of the shadows, teaching him how to sway a mob. Vollmer preaches discrimination draped in patriotism and disguises persecution as a fight for survival. The same people who once treated him with contempt now listen and cheer. Nearly 20 years after the Second World War ended, Serling recognised that certain battles weren’t over—and must always be fought.

‘Nothing in the Dark’, season 3, episode 16, written by George Clayton Johnson

An old woman (Gladys Cooper) crouches in the dingy basement of a tenement, her world circumscribed by its narrow walls. She is hiding from Death and has spent (one might say wasted) most of her life doing so. One day a policeman (a young Robert Redford) is shot and wounded outside her door and begs her for help. Despite her fears, she lets him in. Essentially a two-handed play beautifully performed by Cooper and Redford, this episode is deeply moving, a meditation on what makes us human.

‘The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street’, season 1, episode 22, written by Rod Serling

One Saturday afternoon in summer, the residents of a perfectly ordinary suburban street somewhere in the United States find themselves cut off from the rest of the world. The phones and radios are dead. There’s no electricity. And the cars won’t start. It isn’t long before the inhabitants begin to fear they are in the midst of an alien invasion—and turn on one of their neighbours because his car starts running. Prejudice is corrosive, eating away at the residents’ consciences and capacity to reason, encouraging them to panic and surrender to their basest instincts. When anyone can be the enemy, the only way to prove your loyalty is by pointing the finger at someone else. A metaphor for the dangers of mob mentality and a comment on McCarthyism, ‘The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street’ has proven itself one of The Twilight Zone‘s most durable stories, remade for the 2002 run (this time addressing the fear of terrorism), adapted for radio and working its way to the big screen as part of the inspiration for The Mist.

‘The Last Flight’, season 1, episode 18, written by Richard Matheson

Lieutenant William Terrance ‘Terry’ Decker (Kenneth Haigh) of the Royal Flying Corps is flying back from a mission over France in 1917 when he slips through time and touches down at a modern US Air Force base. The commanding officer thinks the whole affair is a hoax, perhaps a plot to assassinate the RAF general who will soon arrive for a routine inspection. But one of his junior officers isn’t sure. For one thing, Decker insists the general is already dead. Lost in more ways than one, Decker is a man consumed by fear, terror as deeply rooted within him as cowardice. And yet, there’s hope. Redemption is always possible for those willing to seek it.

‘It’s a Good Life’, season 3, episode 8, based on a short story by Jerome Bixby, teleplay by Rod Serling

The village of Peaksville used to be in Ohio, until one day a monster made the rest of the world vanish. Electricity and machinery also disappeared—the monster objected to them. The monster objected to Aunt Amy too, transforming her, in Serling’s words, into a “smiling, vacant thing”. Everyone must smile and think happy thoughts; if they don’t, the monster “can wish them into the cornfield” or turn them into grotesque, shambling horrors. The monster is six-year-old Anthony Fremont (Bill Mumy): a child with no compassion, no conscience, no restraint and no limits on what he can accomplish simply by willing it so. ‘It’s a Good Life’ is one of the most disturbing Twilight Zone episodes ever made. Many children think they’re the centre of the universe but Anthony really is. Peaksville under his rule is a dictatorship from which the only escape is death.

‘Time Enough At Last’, season 1, episode 8, based on a short story by Lynn Venable, teleplay by Rod Serling

All cashier Henry Bemis (Burgess Meredith) wants to do is read. A dreamer in a world that has no place for dreams, he peeks out from behind his thick, Coke bottle lenses as if peering at life through a goldfish bowl. Society is hostile but Henry remains defiant in his shambling way, even when his wife nearly breaks him by defacing every page of a poetry anthology and tearing the book to pieces before his eyes. One afternoon he sneaks into the bank’s vault to read and emerges to discover that the entire city has been obliterated by a nuclear bomb. The episode builds to a notoriously savage conclusion that wouldn’t have been out of place on the more misanthropic The Outer Limits. Even in solitude, a man might not know peace.

‘Walking Distance’, season 1, episode 5, written by Rod Serling

In its earliest sense the word ‘nostalgia’ meant acute homesickness. Martin Sloan (Gig Young) would understand that. Lost and confused, he longs to go home again. One Sunday he does just that and finds everything exactly as he remembers it. Set to a heart-rending score by Bernard Hermann, this episode always brings a lump to my throat. There are moments when many of us have wished, however fleetingly, that we could retreat to a place where we once felt safe and loved. Yet even if we could, Serling suggests we ought not to stay. Spend too much time looking behind you and you ignore what might be ahead.

‘And When the Sky Was Opened’, season 1, episode 11, based on a short story by Richard Matheson, teleplay by Rod Serling

Two astronauts fly an experimental craft into space, briefly disappearing from radar before reappearing and crashing into the desert. Except according to one of the men, Colonel Clegg Forbes (Rod Taylor), there were actually three astronauts. One of the men vanished overnight and only Forbes remembers him. The idea that you could be erased from existence and no one, not even your friends and family, would notice is terrifying. Even worse, your memory could contradict reality and there would be no way to prove reality wrong.

‘Little Girl Lost’, season 3, episode 26, written by Richard Matheson

Imagine you could hear your child crying out for help but no matter where you looked, you couldn’t find her. That’s the nightmare Chris and Ruth Miller (Robert Sampson and Sarah Marshall) awake to one night when their daughter Tina (Tracy Stratford) inexplicably disappears. Their friend Bill (Charles Aidman), a physicist, discovers that a wall in her bedroom has become a portal to another dimension—and Tina has fallen through. Tense, eerie, surreal and the inspiration for Poltergeist.

‘Eye of the Beholder’, season 2, episode 6, written by Rod Serling

A young woman, Janet Tyler (Maxine Stuart), lies in a hospital bed, her head wrapped in bandages, awaiting the outcome of a government-mandated procedure that’s supposed to make her look normal. If the procedure doesn’t work, the only option left is state-sponsored segregation. As a doctor tells her, not unsympathetically, she can’t expect to live alongside ordinary people. Serling’s script dissects the notion of the Other: who gets to decide who is normal and who is undesirable. Desperate to be part of a world that has always held her at arm’s length, Janet yells that the state hasn’t the right to make ugliness a crime. Yet no one else really questions society’s treatment of her. An indictment of discrimination that forces you to re-evaluate every idea you had going in, ‘Eye of the Beholder’ is The Twilight Zone at its best.

Leave a Reply