At 5:16 PM on 23 November 1963, a new science fiction show premiered on the BBC. What started out as a mild curiosity in a junkyard has grown into the world’s longest-running science fiction series, a grand adventure spanning over 50 years across television, radio, comics, videogames and novels (plus a marvellous, fan-made stop-motion animation series).

A quick Doctor Who primer. The Doctor is a Time Lord, an alien from the planet Gallifrey who has the ability to regenerate, completely changing her body, personality and most recently, gender. She (formerly he) travels through time and space in the TARDIS (Time and Relative Dimension in Space), a living ship that looks like a 1960s British police telephone box and is bigger on the inside. She saves planets on a daily basis, traditionally with a companion or two in tow—the Watsons to her Holmes. There’s a remarkable amount of running involved.

Jodie Whittaker makes her debut today as the Thirteenth Doctor, the first woman and fourteenth actor to play the role. (No, that isn’t a typo. It’s a long story.) In the protracted wait since the Twelfth Doctor’s last episode last Christmas I’ve been revisiting my favourite stories and exploring new ones. What’s wonderful and daunting about the Whoniverse is how vast it is. At its centre are the show and its many spinoffs; on the outer reaches is an expanded universe of stories loosely connected with the show, but not considered part of the official canon. It’s to the latter category that Dr. Who and the Daleks and Daleks – Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. belong. Released near the beginning of the show’s run, the films were made largely to cash in on its popularity—specifically that of its first monsters, the Daleks.

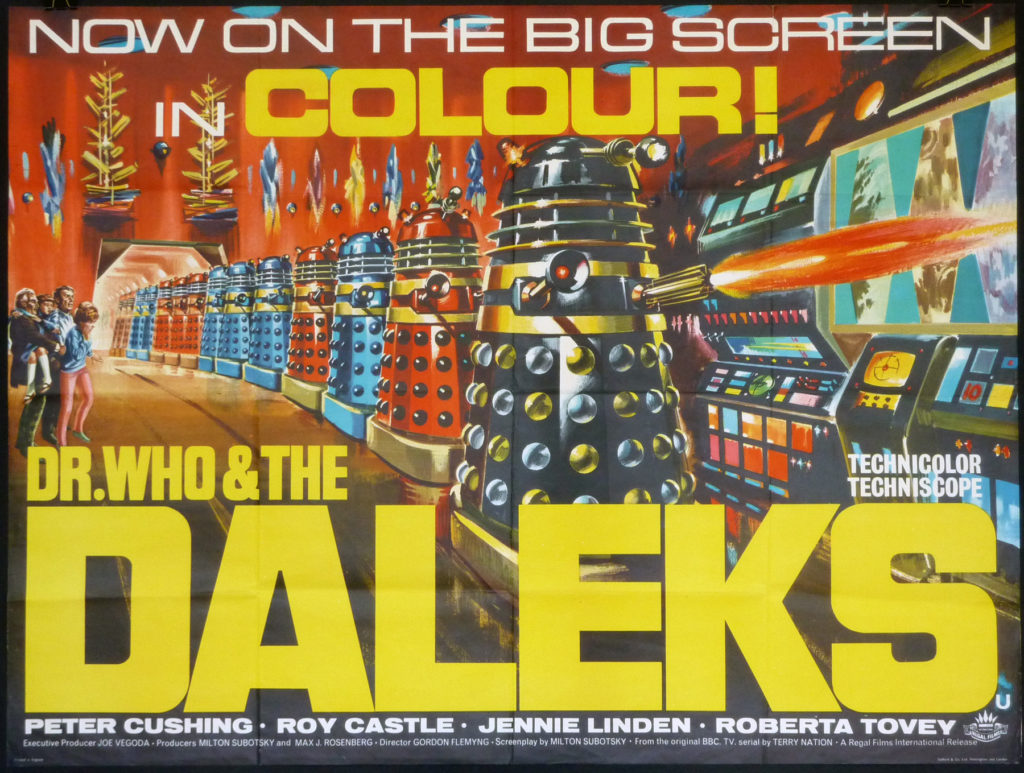

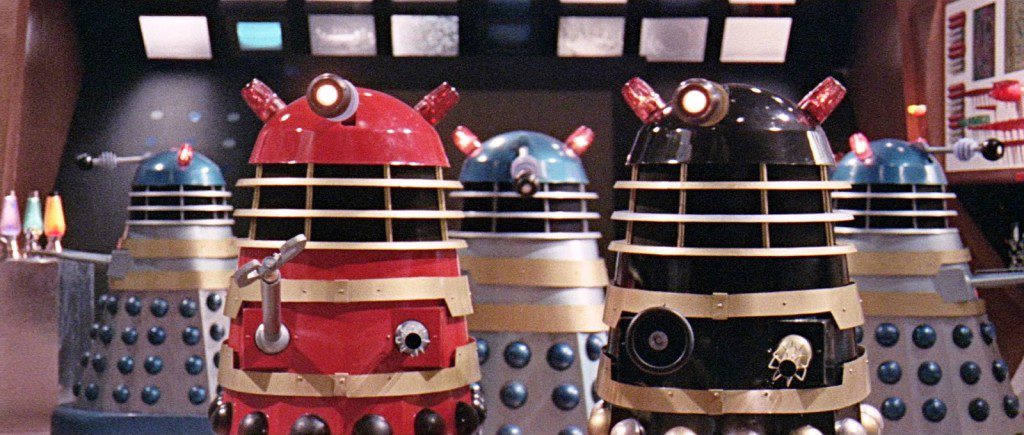

As synonymous with Doctor Who as the TARDIS, the Daleks are a race of vicious, frequently homicidal alien mutants encased in armoured shells. Created by Terry Nation, they appeared in the First Doctor’s second serial, ‘The Daleks’, and became an immediate phenomenon, terrifying a generation of children and cementing the show in the public imagination. Dalekmania swept the UK. There were toys, pencils, books, even—according to the BFI—a Dalek cake for Christmas 1965, courtesy of Selfridges. The word ‘Dalek’ eventually made it into the Oxford English Dictionary. Seeing the potential for a big-screen hit, producer Milton Subotsky approached Nation and the BBC and secured the film rights for ‘The Daleks’, with options for possible sequels.

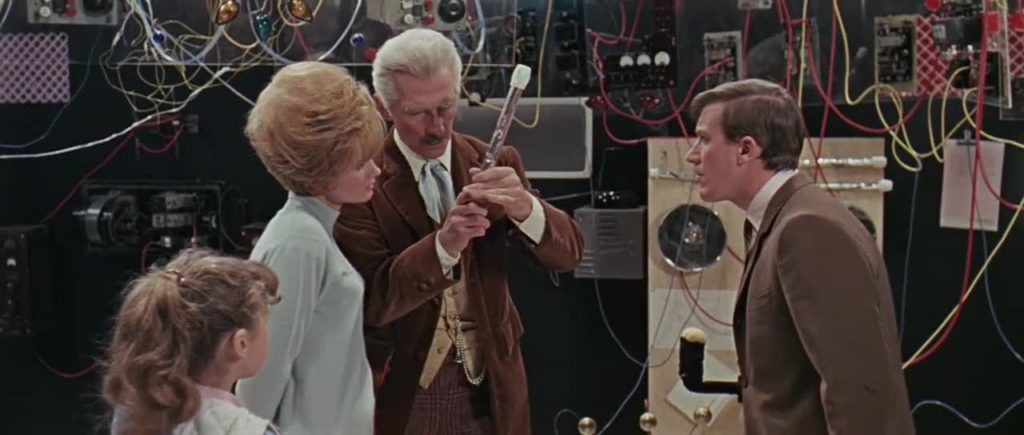

Dr. Who and the Daleks is based on Nation’s original serial but makes several changes. The Doctor is no longer an alien but an absent-minded human inventor called Dr. Who (Peter Cushing), who lives with his granddaughters Susan (Roberta Tovey) and Barbara (Jennie Linden). He invents a time and space machine called Tardis (no block capitals or definite article), which still looks like a police phone box, but is bigger on the inside only in the sense that it contains one large room. No explanation is given for the phone box shape—I suspect the producers kept it for marketing purposes. One evening Barbara’s boyfriend Ian (Roy Castle) comes calling and while Dr. Who is showing him around Tardis, the young man accidentally falls on a lever, dematerialising the ship. Yes, the entire adventure begins because Ian is clumsy. Tardis lands on an alien world and the travellers are soon fighting to escape the clutches of the Daleks.

Gordon Flemyng’s film has one advantage over the show: a bigger budget. Dr. Who and the Dalek’s production design trumps the BBC’s, with the petrified forest the ship materialises in and the entrance to the Dalek city particular standouts. What’s more, unlike Doctor Who at the time the film wasn’t shot in black and white, which leads to its main attraction: the first chance for audiences to see the Daleks in colour. Red! Black! Blue and grey! Although the show switched to colour with the Third Doctor in 1970, the Daleks wouldn’t be this brightly coloured in the series until the Eleventh’s tenure in 2010.

Subotsky’s script (he also co-produced the film) follows Nation’s plot but sacrifices characterization for comedy. His Dr. Who is an affable, wide-eyed explorer, a far cry from the irascible, sometimes selfish curmudgeon William Hartnell made famous. Cushing is as solid as ever but Subotsky and Flemyng give him nothing to work with. What we see is less a man fighting for survival and more one dismayed that a family outing has gone wrong. The real loser however is Ian, who is transformed from William Russell’s brave, compassionate hero into a cowardly buffoon. This might have worked if the comedy wasn’t so feeble: one gag revolves around him trying to walk through a door. Surprisingly Susan, reimagined as a little girl, is more competent than her teenaged television counterpart.

But back to the main attractions. It takes skill to make Daleks threatening. They are, after all, glorified pepper pots with plungers for arms. Part of what makes them so unnerving in Doctor Who is the way the actors react to them. When Elisabeth Sladen, who played Sarah Jane Smith, one of the show’s longest-running companions, weeps in terror at the sight of them in ‘The Stolen Earth’, you know everyone on screen is in mortal danger. In Dr. Who and the Daleks the actors treat them like a mild inconvenience.

Nevertheless, the film made money, enough to immediately justify a sequel.

The awkwardly titled Daleks – Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. loosely adapts Nation’s 1964 serial ‘The Dalek Invasion of Earth’. It’s an improvement on the previous film, in the sense that sluggish action is an improvement on tedium. Dr. Who and Susan are back but Ian and Barbara have mysteriously vanished, replaced by the Doctor’s niece Louise (Jill Curzon) and a young policeman named Tom Campbell (Bernard Cribbins, who would go on to play a companion in the show 40 years later). Any hopes that Daleks will be less cheesy than its predecessor are immediately dashed: it opens with a suspicious character lurking in a parked car at night, while a riff on Bach’s ‘Toccata and Fugue’ plays. The man turns out to be a thief who attacks Tom so he and his gang can escape. Tom staggers over to a police phone box to call for help. Except the box is Tardis and he and the Whos end up in 2150, in a London overrun by the Daleks.

Having a policeman join the Tardis crew by mistake is clever. Tegan Jovanka, a companion on the show some 20 years after the film was released, first ended up in the TARDIS because she mistook it for an actual police box.

Sadly, this is the film’s only flash of inspiration. Flemyng and Subotsky, with additional material by David Whitaker, rework Nation’s gut-wrenching story—still regarded as one of the best in the show’s history—into a mishmash of lazy plotting and lazier jokes. Take the first scenes in future London. In Nation’s serial, the TARDIS crew explores a decaying city and finds a poster warning citizens not to dispose of bodies in the Thames. In Subotsky’s version, Tom comes to the bumbling realisation that he isn’t in ‘his’ London anymore and the equivalent poster is an advert for Sugar Puffs cereal. (Quaker Oats Company, then makers of Sugar Puffs, partly financed the film in exchange for a merchandising deal.) Worse, Flemyng’s film plays the Robomen, human beings the Daleks convert into zombie-like slaves, for laughs. Trapped on a Dalek saucer, Tom tries to hide in the Robomen’s ranks as they march, sit and eat in unison—all set to an obnoxious faux-Tom and Jerry score.

There are bright spots. Both Godfrey Quigley as Dortmun, a resistance fighter, and Philip Madoc as the smuggler Brockley, manage to find treasure among the trash. Madoc is particularly good, conveying more with a smirk than with any of the lines he’s given. Fortunately, he found his way onto Doctor Who several times, most notably as the villain in ‘The Brain of Morbius’. And once again, the film has more money to spend than its television equivalent, giving us flashier special effects and fight scenes.

But a big budget means little without imagination. ‘The Tomb of the Cybermen’ was made for a fraction of Daleks’ budget and broadcast the year after the film was released. Seen 51 years later, the Cybermen’s costumes aren’t that convincing, nor are the raygun gothic sets. Yet the serial remains a fan favourite because it has a heart, a spark of wonder that matters more than silly costumes. Incidentally, wonder is completely absent from Flemyng’s film.

Daleks was a box office disappointment, putting an end to the Dalek films. Simultaneously bad adaptations and bad stand-alone films, they now exist as curios, sought out by inquisitive Whovians, serious Peter Cushing fans and presumably people with a passion for sci-fi ephemera. Dr. Who and the Daleks and Daleks – Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. aren’t just proof that Subotsky and Flemyng didn’t understand what makes Doctor Who special. They’re proof they didn’t even try.

Leave a Reply