No, not that Ben-Hur– the other one. Three decades before MGM’s mighty, Technicolor sword-and-sandal epic starring Charlton Heston, there was MGM’s mighty, black-and-white sword-and-sandal epic starring Ramon Novarro. Both are adaptations of the same novel, Lew Wallace’s 1880 best-seller Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ and, naturally, feature the most magnificent chariot races ever committed to film. News of the 2016 remake threatened by Roma Downey and Mark Burnett- the same team responsible for the History channel miniseries The Bible and its tepid offshoot Son of God– filled me with dread. But since the 1959 film I adore was also a remake, I felt obliged to see the original. Besides, what better way to celebrate MGM’s 90th anniversary than with the film which cemented its reputation for lavish spectacles.

Judah Ben-Hur (Ramon Novarro) is a wealthy Jewish prince living in 1st century Jerusalem with his mother and sister. Although he resents the Roman occupation of Judea, he is delighted when his childhood friend Messala (Francis X. Bushman, looking a tad too old for the part) arrives as tribune of the new governor’s legions. Sadly, Messala isn’t the boy the Hurs remember: convinced of Rome’s superiority, he has grown as arrogant and boorish as any of the foot soldiers who swagger through the city. The two men quarrel and part. Later, Judah and his family are watching the governor, Gratus, parade through the streets when a tile slips from their roof and hits Gratus. Messala quickly realizes that it was an accident, but decides to make an example of the Hurs. He imprisons Judah’s mother and sister and condemns Judah himself to the galleys as a slave. Judah is outraged by Messala’s betrayal and swears his revenge.

It is impossible to watch this Ben-Hur without thinking of its shinier Technicolor twin. To be fair, the film has much to recommend it- just not enough to eclipse my memories of the Charlton Heston epic.

One major obstacle is this version’s almost complete lack of subtlety. The opening intertitle informs us that “Pagan Rome was at the zenith of her power” and “Jerusalem the Golden, conquered and oppressed, wept in the shadow of her walls”. Not long after, we see some Roman centurions openly stealing fruit from a market stall, while another grabs a woman by her hair and shoves her to the ground. When Messala finally turns up, he struts and preens and pontificates without any of the intelligence or genuine human feeling that made Stephen Boyd’s incarnation so compelling. “My friend Messala has become a Roman,” Judah cries in dismay. “And why not? To be a Roman is to rule the world! To be a Jew is to crawl in the dirt!” Messala replies. Boyd’s Messala is a creature twisted by ambition and hatred until he betrays those he once loved; Bushman’s has about as much depth as Dick Dastardly in The Wacky Races.

This clumsiness creeps into many of the film’s religious scenes too. The movie is sub-tilted A Tale of the Christ and director Fred Niblo treats Jesus with understandable reverence. Key events in Christ’s life are depicted in two-strip Technicolor, striking amidst all the black and white, and his dialogue is drawn directly from the Gospels, displayed on intertitles made to look like weathered parchment. But there’s a fine line between earnest solemnity and accidental comedy. Take the scene in which Joseph and Mary arrive in Jerusalem on their way to Bethlehem. Mary notices a woman holding a baby in her arms and, for reasons that aren’t made clear, leans over and wipes the baby’s head. Perhaps she was mopping the sweat from its brow? The mother is irritated, until she gazes into Mary’s eyes and apparently realizes what a wonderful woman Mary is. Since Niblo just cuts between close-ups of a beatific Mary and an increasingly rapturous mother, it’s hard to know what’s going on. I giggled. The director also bungles my favourite aspect of the religious scenes, that the audience never sees Jesus’ face. Christ’s anonymity is a beautiful concept, until Niblo self-consciously recreates Da Vinci’s Last Supper and hastily throws a disciple into the foreground to hide Jesus. The divine halo still peeking out from behind the disciple’s head is the last, ludicrous touch.

After all of this, you might be wondering what I did like about Ben-Hur. Well, Ramon Novarro for one. His version of Judah is proud, warm, generous and at first, endearingly young. Watch and marvel as he chases after Esther’s (May McAvoy) errant pigeon and makes a hilariously contrived meet-cute scene still seem charming. When the Roman soldiers break into the Hurs’ home and drag Judah away from his mother, you can see the panic and rage in Novarro’s eyes. But his best work is in the scene where Judah is marching to the galleys. His lips parched, skin cracked and body streaked with scars, Judah begs the guards for water from a nearby well. One of them fills a gourd and waves it in front of Judah’s face, only to empty it onto the ground. Judah buries his cheeks in the dust. It’s a moment of complete desolation and it’s deeply moving.

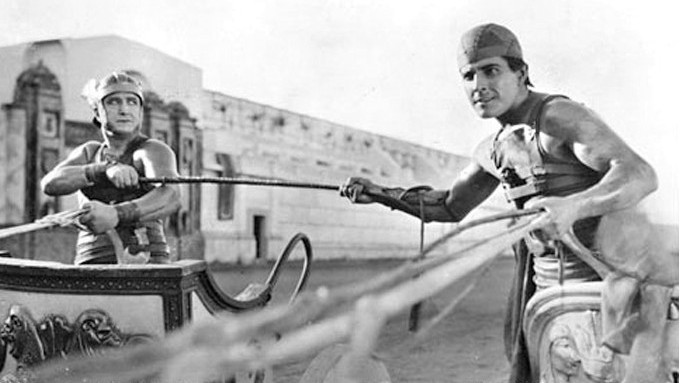

Besides Novarro, the main attraction is the chariot race. Nearly ninety years on, this sequence remains a towering achievement. The set, built in Culver City, is enormous and populated with the proverbial cast of thousands. There’s a special thrill in knowing that everything, from statues to spina to crowds, is ‘real’: no feeble CGI here. Cameras (forty-two of them) capture the race from every possible angle, including under horses’ hooves and legs and chariot wheels as they thunder past. William Wyler was an assistant director on the film and recreated the race almost shot for shot for his 1959 version. And George Lucas simply restaged it with aliens for the pod race in The Phantom Menace. (Fun fact: Douglas Fairbanks, John Gilbert, the Gish sisters, the Barrymore brothers, Harold Lloyd and Joan Crawford all played spectators in this scene. That has to be one of the starriest casts of extras in history.)

The 1959 version of Ben-Hur trumps its twenties’ counterpart in almost every way- performances, characterization, story structure- but Niblo’s film is well worth seeing. The sets are impressive, Novarro is a solid lead and the chariot race remains one the best action sequences ever made.

Leave a Reply