Late nights, fast talking and even faster typing. To celebrate me making it through my first month of journalism school, here is a fleeting look at the fourth estate on film.

His Girl Friday (1940) The gold standard of newspaper comedies. Wily editor Walter Burns (Cary Grant) is horrified when his star reporter and ex-wife, Hildy Johnson (Rosalind Russell), announces her retirement and impending marriage to a milquetoast insurance salesman (Ralph Bellamy). Burns decides to sabotage their union and lure Hildy back to the typewriter- kidnapping and multiple arrests ensue. Rapid-fire delivery has rarely had a better showcase. Everyone talks and talks fast, often on top of each other, while the plot races forward at a hundred miles per hour. Keep up or like poor Ralph Bellamy, you will be left behind- though hopefully not in jail.

His Girl Friday (1940) The gold standard of newspaper comedies. Wily editor Walter Burns (Cary Grant) is horrified when his star reporter and ex-wife, Hildy Johnson (Rosalind Russell), announces her retirement and impending marriage to a milquetoast insurance salesman (Ralph Bellamy). Burns decides to sabotage their union and lure Hildy back to the typewriter- kidnapping and multiple arrests ensue. Rapid-fire delivery has rarely had a better showcase. Everyone talks and talks fast, often on top of each other, while the plot races forward at a hundred miles per hour. Keep up or like poor Ralph Bellamy, you will be left behind- though hopefully not in jail.

Libeled Lady (1936) William Powell, Myrna Loy, Spencer Tracy and Jean Harlow star in this screwball comedy about an heiress (Loy) suing a newspaper for libel. It is a perfect example of that perennial frustration: the movie that ought to be better than it is. Powell and Loy are remembered as one of the best screen teams Hollywood ever produced and with good reason: their scenes together shimmer. Powell also finds a good foil in Harlow; the two actors were engaged soon after the film was released. Sadly whenever Tracy reappears, he takes a mallet to the soufflé and leaves it in ruins. It isn’t really his fault: the reporter he plays is simply too obnoxious to be entertaining. Do your best to ignore him and you will be left with a fine, wacky comedy.

Libeled Lady (1936) William Powell, Myrna Loy, Spencer Tracy and Jean Harlow star in this screwball comedy about an heiress (Loy) suing a newspaper for libel. It is a perfect example of that perennial frustration: the movie that ought to be better than it is. Powell and Loy are remembered as one of the best screen teams Hollywood ever produced and with good reason: their scenes together shimmer. Powell also finds a good foil in Harlow; the two actors were engaged soon after the film was released. Sadly whenever Tracy reappears, he takes a mallet to the soufflé and leaves it in ruins. It isn’t really his fault: the reporter he plays is simply too obnoxious to be entertaining. Do your best to ignore him and you will be left with a fine, wacky comedy.

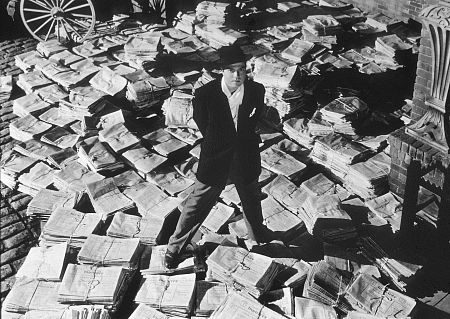

Citizen Kane (1941) The entire plot is framed by a journalist’s search for a story: just what is ‘rosebud’? Kane himself is at his most charming as an earnest young newsman. His desire to make the New York Daily Inquirer as essential to New Yorkers as the gas in their lamps is a wonderfully poetic expression of that deep longing every journalist feels. Your work must matter to people- it must be seen, understood, talked about. It must be important, because it was important to you.

Citizen Kane (1941) The entire plot is framed by a journalist’s search for a story: just what is ‘rosebud’? Kane himself is at his most charming as an earnest young newsman. His desire to make the New York Daily Inquirer as essential to New Yorkers as the gas in their lamps is a wonderfully poetic expression of that deep longing every journalist feels. Your work must matter to people- it must be seen, understood, talked about. It must be important, because it was important to you.

Ace in the Hole (1951) This bold and bitter film was Billy Wilder’s follow up to Sunset Boulevard. Down-at-heel reporter Chuck Tatum (Kirk Douglas) stumbles across a man trapped by a cave-in and milks the story for all it is worth. The police, fellow journalists and the general public are happy to oblige. Douglas is terrifying, delivering a portrait of reckless reporting which stands for a general amorality in American society. It certainly cut too close to the bone for US audiences and critics to bear. The film flopped and was only recognized as a masterpiece later.

A Face in the Crowd (1957) Not so much a film about journalism as it is about the astonishing power of mass media. Southern-fried philosopher ‘Lonesome’ Rhodes (Andy Griffith) catches the eye of radio reporter Marcia Jeffries (Patricia Neal) and rapidly becomes one of the most influential celebrities in America. With great power comes megalomania and Jeffries is appalled by the monster she helped create. Like Ace in the Hole this was a warning for the ages, relatively unheeded on release.

Network (1976) Say it with me: “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this any more.” Over 30 years later this scathing satire of television broadcasting still has the power to shock. In fact the most alarming thing about it is its prescience. Veteran news anchor Howard Beale (Peter Finch) is about to be fired when he announces he will commit suicide live on air. His angry desperation strikes a chord with audiences and he is quickly given his own show. It is reality television and the film only gets uglier from there.

All the President’s Men (1976) Billed as, “The most devastating detective story of this century.” They had a point. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein (Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman respectively) of The Washington Post investigate a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Watergate, and become legends in their own lifetimes. Freedom of the press in its purest form.

All the President’s Men (1976) Billed as, “The most devastating detective story of this century.” They had a point. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein (Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman respectively) of The Washington Post investigate a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Watergate, and become legends in their own lifetimes. Freedom of the press in its purest form.

Broadcast News (1987) This is what The Newsroom wishes it was. Much as I respect Aaron Sorkin, this movie covers most of the same ground he does in ten hours of television, but with greater wit, charm and wisdom. Jane Craig (Holly Hunter) is a brilliant producer; reporter Aaron Altman (Albert Brooks) is her equally clever colleague and best friend. When Tom Grunick (William Hurt) is promoted to their office solely for his looks, neither Jane nor Aaron can hide their disdain. However Jane soon falls for Tom, to Aaron’s dismay. Writer-director James L. Brooks regards relationships and the news industry with a penetrating eye. The love triangle is interesting precisely because it gets tangled up with workplace ethics and the splendid central performances keep you riveted.

Good Night, and Good Luck (2005) Edward R. Murrow (David Strathairn), Fred Friendly (George Clooney) and their crew at CBS News stand up to Senator Joseph McCarthy at the height of the fifties ‘red scare’. Deliberately monochrome- it was shot in black and white- and deliberately old-fashioned, this film harks back to a golden age of television broadcasting and reporting. Murrow and his crew believe in journalism as a vocation- a calling to pursue the truth and present the facts to their audience. With their nation seemingly terrorized by the threat of Communism, they are unafraid to act as its moral conscience and bring it to its senses. Heady stuff for aspiring journalists like me.

Good Night, and Good Luck (2005) Edward R. Murrow (David Strathairn), Fred Friendly (George Clooney) and their crew at CBS News stand up to Senator Joseph McCarthy at the height of the fifties ‘red scare’. Deliberately monochrome- it was shot in black and white- and deliberately old-fashioned, this film harks back to a golden age of television broadcasting and reporting. Murrow and his crew believe in journalism as a vocation- a calling to pursue the truth and present the facts to their audience. With their nation seemingly terrorized by the threat of Communism, they are unafraid to act as its moral conscience and bring it to its senses. Heady stuff for aspiring journalists like me.

Leave a Reply