About two weeks ago, I found myself thinking of Stanley Donen. In the latest debacle surrounding this year’s Oscar ceremony, the Academy had just announced it would be dropping the presentation of four awards, including Best Editing and Best Cinematography, from the telecast—a decision so manifestly absurd and greeted with such derision that it was soon reversed. The fiasco made me think of what had already been lost. The Academy’s three lifetime achievement awards—the Academy Honorary Award, the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award and the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award—were once presented during the main Oscars ceremony. For a few minutes, the parade stopped to honour artists like Cary Grant, Barbara Stanwyck, Peter O’Toole and Myrna Loy. Then in 2009 the presentations were relegated to the untelevised Governors Awards, presumably so the public would be untroubled by further exposure to film history.

I looked forward to the honorary Oscars every year. What I remember most clearly about the 70th Academy Awards, in 1998, isn’t Titanic winning Best Picture and seemingly every other award that wasn’t nailed down. It’s Stanley Donen receiving his Honorary Award with one of the best acceptance speeches I’ve ever seen:

He didn’t just talk, he sang and danced—what could be more magical than that?

Stanley Donen was born on 13 April 1924 in Columbia, South Carolina. Growing up Jewish, he was bullied by anti-Semitic classmates and found escape at the cinema. Fred Astaire was his idol, inspiring him to become a dancer. He graduated from high school at 16 and moved to New York, eventually landing a part in the chorus of the original 1940 Broadway production of Pal Joey, the musical that made Gene Kelly a star. When Kelly began choreographing his next musical, Best Foot Forward, he asked Donen to be his assistant. And when they had both moved West, to Hollywood, Kelly asked him to be his assistant again, on Cover Girl (1944). Together they devised the ‘Alter Ego Dance’, in which Kelly dances with his ghostly reflection. When director Charles Vidor protested that the idea would never work, Kelly and Donen directed it themselves.

In 1949, producer Arthur Freed gave Donen and Kelly their first shot at directing a feature: On the Town. They wanted to film the entire musical on location in New York; Freed would only allow them to be away from the studio for a week. ‘New York, New York’, the film’s infectious opening number, is the result of that week, a love letter to New York City, bursting with life and joy. Kelly was 37; Donen was 25. In 1952, they co-directed Singin’ in the Rain, the best musical ever made. I love every frame.

Donen became an MGM stalwart. He directed Fred Astaire in Royal Wedding, which features him dancing on the walls and ceiling in ‘You’re All the World to Me’. In 1954, Donen made Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. The tale of seven rowdy backwoodsmen in search of wives, Seven Brides was one of only two MGM musicals my grandparents owned on VHS (the other was The Pirate). I nearly wore the tape out. My favourite scene is the barn dance, in which six of the brothers compete for the attention of some local girls. Donen makes full use of the Cinemascope frame, keeping track of as many as six couples and 18 performers at a time, and still finding room for little grace notes, like the girl who curtseys to her partner, then waves to one of the brothers, standing behind her.

The film was a surprise hit, becoming one of the highest grossing films of the year and earning five Oscar nominations, including one for Best Picture.

As the golden age of musicals waned, Donen branched out in other directions. In 1958 he directed and produced Indiscreet, a sparkling romantic comedy and Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant’s second pairing after Notorious (1946). They meet first in Bergman’s flat: she has the dumbfounded look we all would if we turned and unexpectedly found Grant waiting in our doorway. Later, they return after an evening out and walk into her building’s lift. They gaze at each other in silent communion, the climax of a perfect night. Donen worked with Grant again in Charade (1963), this time alongside Audrey Hepburn. As chic as Hepburn’s Givenchy wardrobe, Charade is the best Hitchcock film Hitchcock never made, a soufflé that includes Grant taking a shower, fully dressed, and these immortal lines (by Peter Stone):

Reggie (Hepburn): “Do you know what’s wrong with you?”

Peter (Grant): “No. What?”

Reggie, leaning forward: “Nothing.”

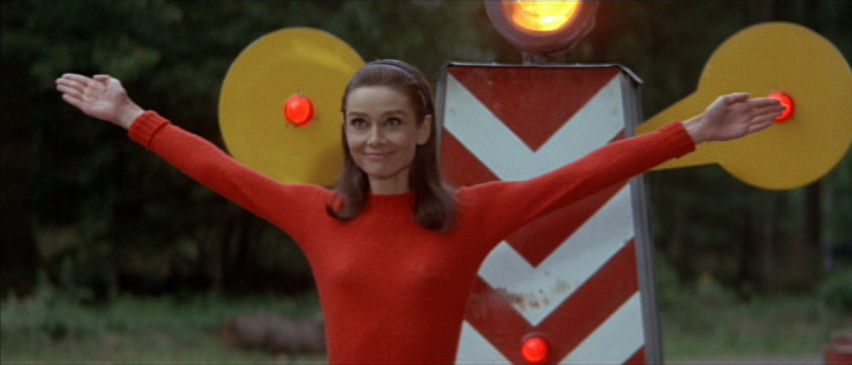

One of my favourite shots of Hepburn comes from another Donen film, the marvellous Two for the Road, a film that’s also been on my mind this month, due to the recent loss of Albert Finney. Hepburn and Finney play Joanna and Mark, two young people hitchhiking through France. After they fail to flag down a ride, Mark suggests they separate, essentially declaring their relationship disposable. Joanna leaves and Mark realises what he’s just thrown away. He keeps walking, only for Joanna to suddenly appear, grinning, from behind a road sign. Hepburn is radiant. It’s a delightful moment, beautifully played by both actors and beautifully directed by Donen.

As a boy, Stanley Donen found joy at the movies. As a man, cinema became his life and he helped create films which brought that same joy to generations of viewers, including me. We are eternally grateful.

Leave a Reply