Happy Father’s Day! As we celebrate fathers of all shapes and sizes, here are a handful of cinematic ones who run the gamut of paternal devotion.

To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) When Scout Finch (Mary Badham) comes home weeping after a disastrous first day at school, her father comforts her with the following advice: “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view. Till you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it.” Sage words from the wisest of men. Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck) is a lawyer in small-town Alabama, a widower raising two children in the midst of the Depression. He not only talks to Scout and her brother Jem (Philip Alford) but listens to them too and takes the time to explain complicated ideas in ways they understand. He believes everyone should be treated equally and is unafraid to act as Maycomb’s moral conscience, defending Tom Robinson—a black man accused of raping a white woman—even in the face of his neighbours’ scorn. To do any less would be anathema to him.

Mr. Skeffington (1944) Job Skeffington (Claude Rains) is the loving, long-suffering husband of Fanny (Bette Davis), a vain socialite who neglects him and their young daughter, also named Fanny (Sylvia Arslan). After the Skeffingtons’ marriage finally collapses, Job takes his daughter out to dinner and tells her he will be leaving her behind with her mother. Job is Jewish; his wife is not. How can he tell his beloved child that taking her with him to Europe will mean exposing her to the horrors of anti-Semitism? He breaks down and Fanny, realising he is trying to protect her, tearfully hugs him. Job and Young Fanny have comparatively few scenes together—despite its title, Mr. Skeffington is a Davis vehicle—but you never doubt the strength of their bond.

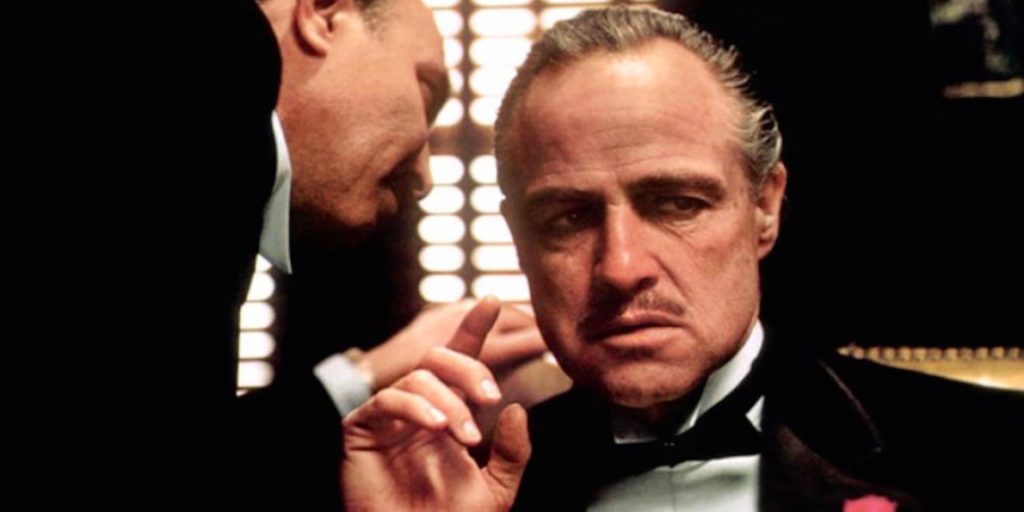

The Godfather (1972) Everyone knows Don Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando) is a family man. One of his families just happens to be a ruthless criminal organization. Vito dotes on his children and genuinely wants the best for them, but sees nothing wrong with violence and intimidation as means to an end. He dispenses judgements in his office, ordering a beating here, a bribe there, then emerges to dance with his daughter on her wedding day. Violence is strictly business; it’s his family that matters.

The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934) Edward Moulton-Barrett (Charles Laughton) presides over his brood of six sons and three daughters like a despot. In his own twisted imaginings he is a caring and attentive father. In reality, he demands absolute obedience and does his best to prevent his children from forming any close attachments. He is extremely possessive of his eldest daughter, Elizabeth (Norma Shearer), a frail poet who has the misfortune to be his favourite. The Hays Code dictated that Edward’s unhealthy interest in his daughter could only be hinted at. But as Laughton himself said, “They can censor it all they like, but they can’t censor the gleam out of my eye.”

Edward, My Son (1949) The entire film revolves around Edward Boult, whom we never see. Instead we become acquainted with his father, Arnold (Spencer Tracy), whose love for his son becomes a fixation that brings out the worst in both of them. Arnold’s obsession drives his rise from small businessman to wealthy financier and his slide into heartless amorality. Edward grows up spoilt and cruel, but Arnold can’t see that. To him his son is, was and will always be perfect.

The Sound of Music (1965) There are icebergs drifting in the North Atlantic less intimidating than Captain Georg von Trapp (Christopher Plummer). A widower, he runs his household like a ship, dressing his seven children in quasi-naval uniforms and training them to answer at a whistle’s blast. His military sense of discipline coexists with a cutting wit. Yet beneath the froideur is a loving man who has simply lost touch with his children. Maria (Julie Andrews) reintroduces him to music, and with it, his family.

The Kid (1921) The Tramp (Charlie Chaplin) finds a baby abandoned in an alley and, after a few false starts, adopts him. The boy (Jackie Coogan) becomes his partner in small scams that put food on the table. They are poor but happy. Then the authorities discover the Tramp isn’t the boy’s birth father and come to take him to an orphanage. The Tramp races after them, fighting off a policeman and scrambling across rooftops to rescue his son. Their reunion is one of the most beautiful ever filmed.

The Lion in Winter (1968) King Henry II (Peter O’Toole) is a successful ruler and a miserable excuse for a father. Of his three surviving sons, he belittles the eldest, spoils the youngest and ignores the one in the middle. To Henry, backstabbing is a blood sport and he invites his sons and their mother, his estranged wife Eleanor (Katharine Hepburn), to Christmas court at Chinon partly for the pleasure of manipulating them all. He has known his children all their lives but they still have the power to surprise him—as Henry discovers to his cost.

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) Nothing impresses Professor Henry Jones (Sean Connery). Not even his son Indiana (Harrison Ford) rescuing them both from a castle filled with Nazis, jousting on a motorcycle with a flagpole for a lance. Henry was a distant father, more interested in the quest for the Holy Grail than in his child. Now Junior has grown up and neither sees much to admire in the other. They slowly learn better. James Bond was a partial inspiration for Indy, so naturally Steven Spielberg and George Lucas asked Connery to play his father. Underneath his tweedy exterior Henry Sr. is as magnificent as his son. Who else could save the day with Charlemagne?

Leave a Reply