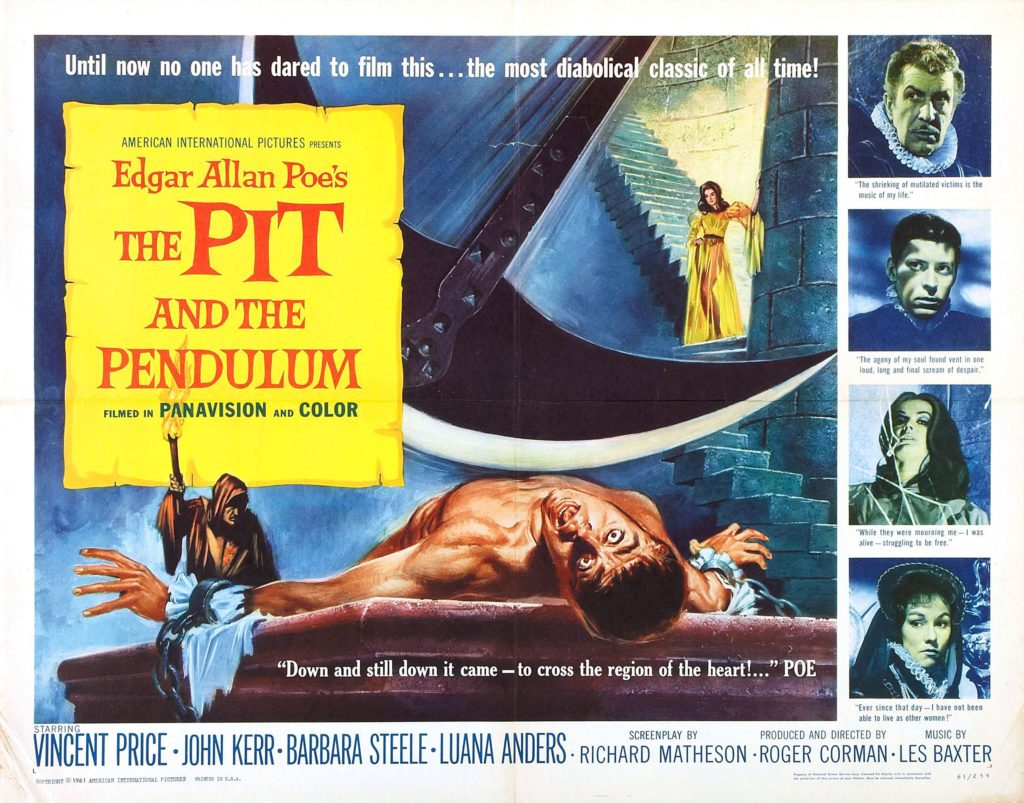

How does a man go mad? In The Pit and the Pendulum the answer is inch by inch, like shadows creeping up a stair. A disintegrating mind is as terrifying as a haunted house.

Francis Barnard (John Kerr) isn’t interested in ghosts. They interfere with facts. Sent word that his sister Elizabeth (Barbara Steele) has died suddenly, he travels to his brother-in-law Don Nicholas Medina’s (Vincent Price) castle in Spain to demand an explanation. Nicholas and his younger sister Catherine (Luana Anders) are welcoming but evasive, claiming Elizabeth died of a rare blood disorder, but shying away from the details. Suspicious, Francis swears he will not leave until he discovers exactly how his sister died. The Medinas have a lot to explain, starting with the torture chamber in the dungeon.

The Pit and the Pendulum was the second of Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe films and the one which perfected the formula: dark secrets, horrors from beyond the grave and Vincent Price. Speaking before a screening at Metrograph recently, Corman explained that American International Pictures couldn’t wait to adapt another Poe story. “There was only one problem,” he said. “They were not just short stories. They were really short.” (Flip through the Penguin Classics edition of Poe’s stories and you’ll find ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’ is little more than 13 pages long.) Screenwriter Richard Matheson’s solution was to use Poe’s tale as the script’s third act, then create a new narrative leading up to it with elements borrowed from other Poe stories. The result is an elaborate gothic horror that barely resembles Poe’s sparse original, but works in its own right.

One of Corman’s theories was that Poe’s stories all sprang from the writer’s unconscious and should be staged accordingly. “The unconscious mind gets its information from the eyes and ears, but does not understand reality,” he said. So he shot mostly on sets and avoided the real world. The Pit and the Pendulum takes place largely indoors, with a brief prologue of Francis approaching the castle by carriage. Corman filmed Kerr on location on the Palos Verdes coast, but the roiling sea feels more like a nightmare divorced from reality. (Interestingly The Tomb of Ligiea, the most naturalistic of Corman’s Poe films, is also the last.) The flashback sequences dredging up the castle’s past are especially stylised, tinted in spectral blues and pinks.

Nicholas’ castle isn’t as monstrous a presence as the house of Usher, but it’s hardly benign. Daniel Haller’s sets, cobbled together from bits and pieces of other productions—the film’s budget was notoriously low—are steeped in gloom, particularly the pendulum and the pit. As the pendulum swings closer, Corman raises the tension by cutting to the pit’s other feature of interest: a crowd of hooded, red-eyed figures painted on the walls. According to Corman, the production finished shooting an hour early and in true ‘waste not, want not’ fashion, he decided to fill the time by getting in some close-ups of the pit.

Of course the best reason to see the film isn’t the sets or the script; it’s Vincent Price. To see Nicholas is to see a nervous breakdown in slow-motion and few actors convey spiritual torment better than Price. Don Medina is a man who expects retribution to fall from the heavens at any moment. It’s this air of guilt that triggers Francis’ suspicions. But Nicholas’ remorse has less to do with Elizabeth’s death and more with a general, all-purpose shame—self-flagellation for the sins of his evil father, Sebastian. Catherine tells Nicholas “his depravities are not yours”, but that doesn’t matter. Grief over Elizabeth nudges him further into madness. The film offers two Vincents for the price of one, so to speak, as he also plays Sebastian. While Nicholas is a good but troubled man, Sebastian was a member of the Spanish Inquisition and installed the castle’s torture chamber. Price plays him with glee.

The rest of the cast is a mixed bag. Francis is a sturdy Englishman with little use for imagination, but it’s difficult to tell how much of his stolidity is intentional and how much is due to Kerr’s stiff performance. Barbara Steele is memorable with minimal screen time and a dubbed voice (Corman didn’t think her Cockney accent suitable for an aristocrat). Luana Anders’ Catherine is an appropriately dignified counterpart to Nicholas’ hysteria and Anthony Carbone gives Dr. Leon, increasingly concerned for his friend Nicholas’ welfare, a reassuring firmness.

The Pit and the Pendulum was a hit with critics and audiences on release and remains one of the most popular entries in Corman’s Poe cycle. It’s stylish and imaginative, buoyed by the ingenuity of its crew, and benefits enormously from Vincent Price. Sit back and watch the pendulum swing.

Leave a Reply