As 2018 ticks to a close, time for one more list. These are my favourite discoveries of the year—films that aren’t new, but were new to me.

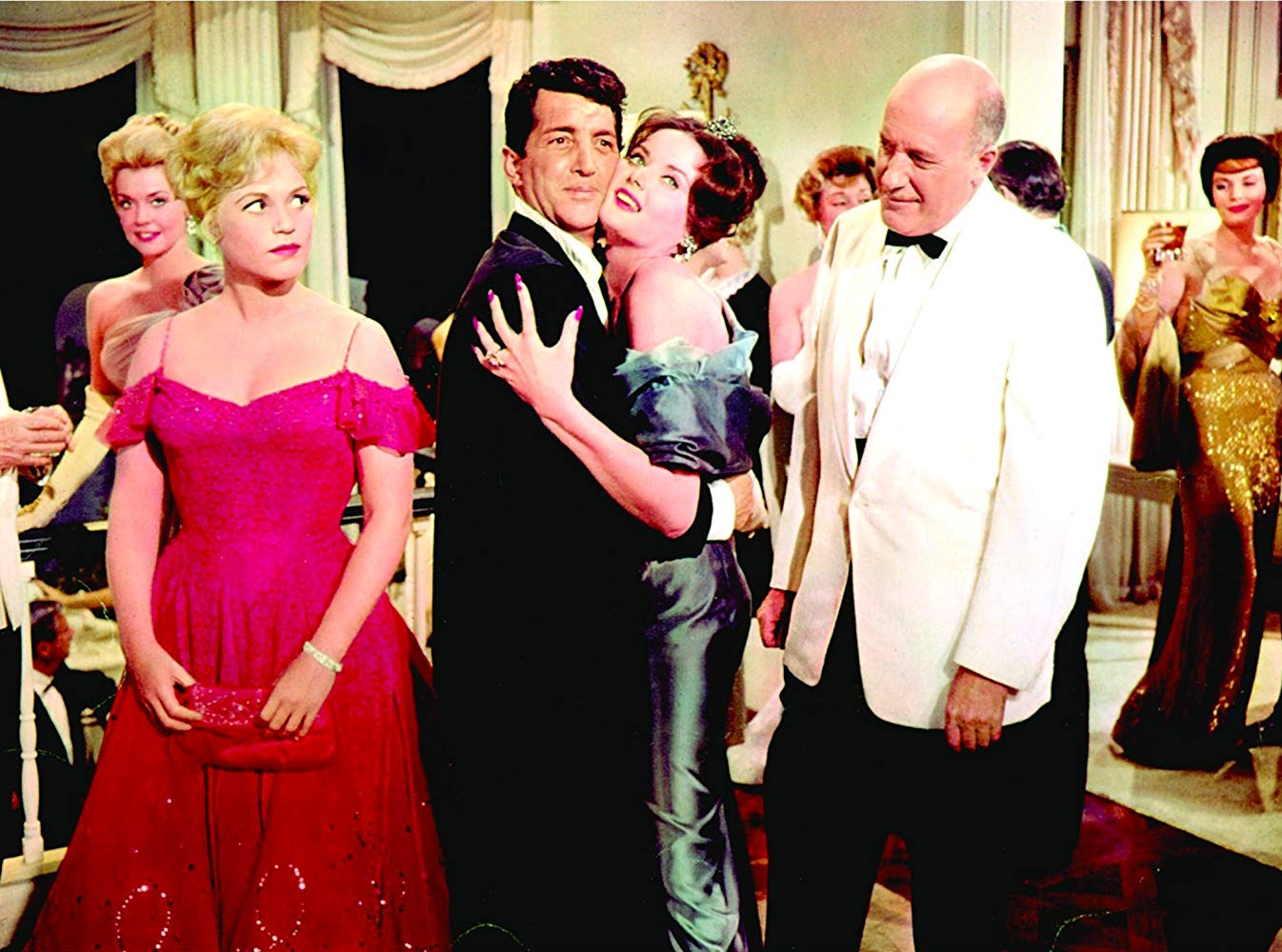

Bells Are Ringing (1960) A musical featuring the combined talents of Judy Holliday, Dean Martin, Vincente Minnelli, Betty Comden and Adolph Green. This film is so easy to love I’m amazed it took me years to see it. Reprising a role that won her a Tony on Broadway, Holliday plays Ella Peterson, a switchboard operator for a telephone answering service who can’t help getting involved in her clients’ lives. There’s the struggling actor trying to be the next Brando, the little boy for whom she pretends to be Santa Claus and Jeffrey Moss (Dean Martin), a playwright she secretly has a crush on, but who thinks she’s a sweet old lady and has nicknamed her ‘Mom’. When she goes to Moss’ apartment to deliver a message, she finally meets him face to face but under an assumed name. Cue confusion and songs on an airhose.

As joyous as Bells is, it’s also, sadly, a film tied to several endings. It was the last film produced by MGM’s Freed Unit, the happy band that gave us An American in Paris, Gigi, On the Town, The Band Wagon and Singin’ in the Rain. It was the thirteenth and last time Vincente Minnelli and producer Arthur Freed worked together. It was also Judy Holliday’s last film; she was already ill during filming and would die of cancer five years later.

The Devils (1971) In 1632, a group of nuns at the Ursuline convent in Loudun, in western France, accused the local priest of bewitching them. The priest was found guilty and burned at the stake. Ken Russell’s film, based partly on Aldous Huxley’s book on the incident, is a descent into Hell—a nightmare which begins with Vanessa Redgrave’s hunchbacked, repressed nun lusting after Oliver Reed’s dissolute but otherwise well-meaning priest. Notoriously violent and disturbing, the film was banned in several countries and is almost impossible to find on DVD. I saw it courtesy of the late, lamented FilmStruck. Russell goes to extremes, but does so as part of his indictment of hypocrisy, hysteria, exploitation and greed. Loudun is a sink hole which stands for the corruption of an entire society. You don’t watch The Devils so much as make it through to the other side.

Enchanted April (1991) Four disparate women escape rain-sodden London for a month’s holiday in a castle in Italy. Mike Newell’s film starts as a quiet character study then blossoms into something magical. The wonderful ensemble cast includes Miranda Richardson, Josie Lawrence, Alfred Molina, Jim Broadbent, Michael Kitchen and Joan Plowright.

The League of Gentlemen (1960) A manhole opens late at night on a desolate street. Out pops a man in a dinner jacket, who climbs into a Rolls-Royce and drives away. The League of Gentlemen is a sly commentary on post-war Britain that also happens to be a caper film. Disillusioned after being forced into early retirement, Lieutenant-Colonel Hyde (Jack Hawkins) assembles a gang of ne’er do well ex-soldiers—including Roger Livesey, Richard Attenborough, Bryan Forbes and Robert Coote—to pull off a million-pound heist. The film is a national treasure in Britain, the inspiration for both the comedy troupe of the same name and Alan Moore’s comic The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (though the less said about the comic’s spinoff film the better). All the performances are excellent, but Nigel Patrick’s Major Race is a scoundrel after my own heart.

Mafioso (1962) For three-quarters of its running time, Mafioso is a barbed culture clash comedy about a Sicilian factory manager, Antonio Badalamenti (Alberto Sordi), visiting his hometown after many years and introducing his sophisticated, northern-Italian wife to his more rustic family. Then director Alberto Lattuda yanks the ground from beneath your feet and sends you hurtling, like Antonio, into the abyss. The term Cosa Nostra translates as ‘Our Thing’. In Mafioso, everyone in Antonio’s village is complicit, even his own family. It doesn’t matter how long he’s been away: the truth is he never really left.

Shame (1968) A husband and wife, Jan (Max von Sydow) and Eva (Liv Ullmann), living in an unidentified country, try to survive as a civil war rages around them. They keep their heads down and stay out of politics, but are still accused of sympathising with the enemy and forced to flee. I saw this when it was screened in March as part of Film Forum’s Ingmar Bergman centennial retrospective and it still haunts me, especially the final scene.

The Silver Cord (1933) I know I keep going on and on about FilmStruck, but it really was an empirical good. Days before the site folded, its programmers put up a batch of Irene Dunne films that included The Silver Cord, a ludicrously rare film that hasn’t been shown on television in over 20 years. Scientist Dunne meets and marries Joel McCrea, an architect, while they are both studying in Germany, then goes home to the US with him to meet his family. Said family consists of a younger brother (Eric Linden), the brother’s fiancée (Frances Dee) and, unfortunately, a manipulative, domineering mother (Laura Hope Crews) with an unhealthy attachment to her sons. A tightly-wound family drama, the film is a fantastic showcase for all three actresses.

Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971) “There are times when nothing has to be better than anything.” Alex Greville (Glenda Jackson), a woman in her thirties, and Daniel Hirsh (Peter Finch), a middle-aged doctor, are two corners of a love triangle, both involved with Bob Elkin (Murray Head), an artist in his twenties. Alex and Daniel have never met, but know about each other and have agreed to share Bob, reasoning that a little love is better than none at all. A study in loneliness, Sunday Bloody Sunday is profoundly melancholy and deeply humane.

Ran (1985) A warlord sits alone in his fortress as his enemies lay siege to it, heedless of the flaming arrows that fly by his head. He has been the architect of his own destruction. Inspired by Japanese legends and King Lear, Ran (Japanese for ‘chaos’) is one of Akira Kurosowa’s greatest achievements—a monumental epic and a maelstrom of violence and despair. Watch it on the largest screen you can find.

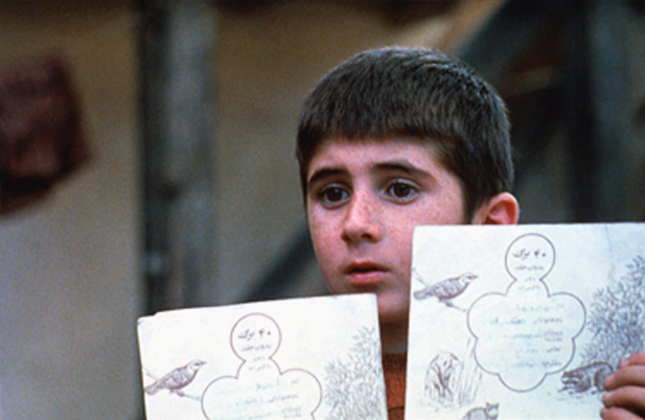

Where is My Friend’s House? (1987) The plot is simple: as he sits down to do his homework, young Ahmed (Babek Ahmedpour) realises he has accidentally brought home his friend Mohamed’s (Ahmed Ahmedpour) exercise book as well as his own. If Mohamed doesn’t hand in the exercise book, complete with homework, the next morning, he will be expelled. So Ahmed decides to return it. But first he must find out where his friend lives. Abbas Kiarostami’s film, which he wrote and directed, took me completely by surprise. Ahmed’s simple act of decency sets him on a quest which soon encompasses issues of duty, loyalty, justice and courage. Above all, the film is a reminder of cinema’s capacity for empathy: by the end of Ahmed’s journey, you feel his experiences as keenly as if they were your own.

Leave a Reply