One of the manifold joys of Cinema Unbound, the landmark Powell and Pressburger series that ran this summer at the Museum of Modern Art, was the opportunity to see some of Michael Powell’s earliest work as a director.

Between 1931 and 1936, Powell directed nearly two dozen films, the majority of them ‘quota quickies’: cheaply made features, produced to fulfil a legal requirement that British cinemas screen a certain quota of home-grown films each year. The films were often limited in production and run time, imposing tight constraints, but also gave him the chance to experiment and showcase his skills.

Around half of Powell’s early films survive. Some are pedestrian, some not—all of them helped set him on a path to becoming one of the most important creative voices in British cinema.

***

After an apprenticeship serving as a jack of all trades with Rex Ingram’s film company on the French Riviera, Powell moved back to Britain in the late 1920s. He worked first as a stills photographer, then as a screenwriter, before finally getting a chance to direct. His first film, the thriller Two Crowded Hours (1931), was a quota quickie and is now, sadly, lost.

Powell began directing his second feature, Rynox, within a week of filming his first. Based on a novel by Philip MacDonald, it chronicles a few days in the life of F.X. Benedik (Stewart Rome), a businessman besieged on multiple fronts. Benedik’s company, Rynox, is foundering, he can barely keep the creditors at bay and a mysterious man named Marsh keeps hounding him. When Benedik confronts him at last, the meeting ends in murder.

Rynox never settles on a tone. One minute it’s a murder mystery from the golden age of detective fiction; another it’s a corporate melodrama that takes broad swipes at British mores, with Benedik a prime specimen of bluff Englishness in the face of unpleasantness. The unevenness is compounded by the convoluted plot. Marsh, for instance, is conspicuously artificial. If the Fagin-cum-Mr. Hyde outfit didn’t clue you in, the outrageously off-putting manners would. Audiences are likely to expect a twist and grow impatient waiting. Also, many of the characters are caricatures: the loving but dim-witted son; the prim and proper secretary; and the servants so hidebound you can practically hear the leather creak. This may have been by design, but it effectively holds them at arm’s length, discouraging viewers from taking more than an academic interest in them.

Two aspects of the production stand out. The first is the fluid camerawork, especially in scenes like the one in which a plan is executed and explained at length, with the camera patiently following along. The second is the marvellous sense of period. Everything from the beautiful Art Deco title which doubles as the firm’s logo to Benedik’s sleek, glistening office feels quintessentially 1930s.

In his autobiography, A Life in Movies, Powell recalled his excitement that Rynox was such a hit, even though he wasn’t quite sure why. C.A Lejeune wrote in The Observer: “Powell’s Rynox shows what a good movie brain can do within the strictest limits of economy…this is the sort of pressure under which a real talent is shot red-hot into the world.” Although her praise of Rynox itself feels a trifle overgenerous now, Lejeune certainly wasn’t wrong about Powell’s talent. He was a director worth following.

***

Powell made Hotel Splendide the next year. The plot is as flimsy as soap bubble: Jerry Mason (Jerry Verno), a lowly clerk who dreams of being a big wig, inherits ownership of the eponymous hotel, but discovers it’s less grand than he imagined. Hijinks involving criminals, false identities and missing loot ensue. A quota quickie co-written by Philip MacDonald (of Rynox fame), Hotel Splendide is a comedy in which the jokes are hammered in to the point of exhaustion. Thankfully, Powell displays his visual invention from the very first scene, which hinges on what is and isn’t reflected in a mirror. His biggest flourish is reserved for the moment when Mason’s dreams collide with reality and quite literally melt away, dribbling down the screen like heated paint and dissolving into fact.

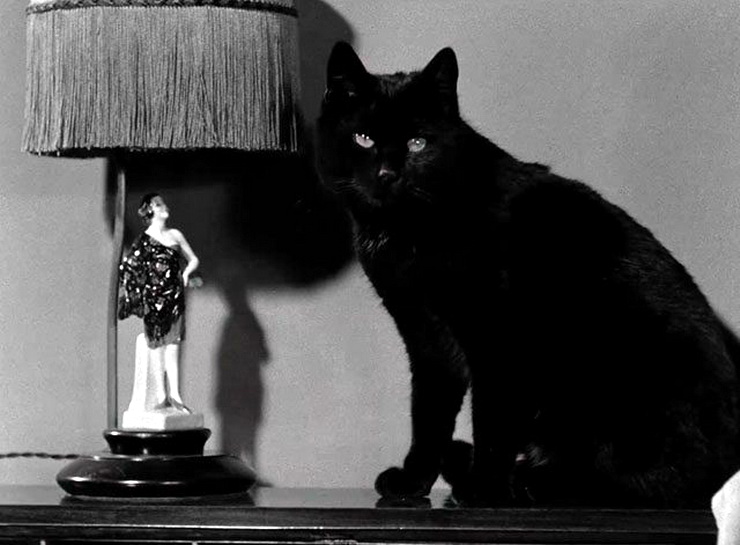

A sequence near the end of the film is worth the price of admission. One of the villains goes by the moniker Pussy and proves himself an unexpected forerunner of Blofeld: he appears with his face shrouded in darkness, accompanied by his pet cat. The cat turns up at a crime scene and the hotel’s staff and guests follow it in single file as it leads them back to its concealed owner. It’s a hilariously absurd scene, made even funnier by the use of Gounod’s Funeral March of a Marionette, now best known as the theme to Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

Hotel Splendide doesn’t merit a mention in Powell’s autobiography, but Jerry Verno does. Powell held him in high regard and worked with him multiple times. In fact, seeing his early films gives you an appreciation for his long memory. Verno has a cameo in The Red Shoes (1948) as the stage door keeper at Covent Garden and Powell persuaded Stewart Rome to come out of retirement for a brief role in …One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942).

***

While Hotel Splendide is intentionally frivolous, Red Ensign is a film with a message. David Barr (Leslie Banks) is a ship builder with big ideas, specifically a radical design for a new ship which will be more efficient to run. Unfortunately, there’s a Depression on: ships are lying idle in yards across the country and no one is inclined to build.

Red Ensign is built around Barr. He is abrasive and consumed with evangelical zeal—Banks doesn’t waste time on trying to court the audience’s sympathy—but he’s also the closest thing the film has to a three-dimensional character and it’s clear he has the filmmakers’ approval. When he runs out of money, he proposes his workmen continue without pay and have faith that he will pay them eventually—an act of extraordinary presumption which the film presents as a rousing moment.

Vexed ethics aside, the film isn’t without interest. Barr’s Clydeside shipyard is viscerally real, a mass of noise, grease, sweat and steel. There are repeated shots of large groups of men hammering and lifting and a montage of the shipyard reopening, empty furnaces suddenly alight and orders for steel flashing across the screen.

Powell was proud of Red Ensign. He not only directed it but also co-wrote the script with Jerome Jackson, inspired by a newspaper article they saw, and likely identified with Barr. A key plot point is a proposed shipping quota which would give the moribund industry new impetus. Powell’s film was a quota quickie tacitly advocating for more investment in British filmmaking. In A Life in Movies, he wrote:

People didn’t know what to make of The Red Ensign [sic]…The elaborate staging of the shipyard, the big, sweeping exteriors, the high standard of performance and the sincerity of the actors, the overall seriousness of my approach to directing our story, made them run for cover.

Red Ensign is a homily exhorting the salvation of the British shipping industry and for all its earnestness, the constant preaching begins to pall. Fortunately Powell would develop finesse later.

***

For much of its running time The Phantom Light doesn’t have much to recommend it. A comic thriller about an allegedly haunted lighthouse just off the Welsh coast, it devotes two-thirds of its running time to following Higgins (Gordon Harker), the new chief lighthouse keeper. He views the Welsh with a disregard bordering on contempt (he’s English and therefore superior) and suffers delusions of grandeur. Harker is so broad he often seems five minutes away from gurning.

Things pick up considerably when Higgins reaches the lighthouse. Powell loved lighthouses and leapt at the chance to direct a film set in one. He visited several for research, as well as Chance Brothers, a Birmingham firm who made lenses for British lighthouses, and settled on using the lighthouse at Hartland Point, in North Devon, for exteriors. In The Phantom Light, he succeeds in conveying the tight quarters—a sudden fire feels like a genuine threat—and makes great use of shadows, such as the menace of one lurking behind the heroes as an assailant prepares to strike. And the climax, which features a rapid-fire montage of a ship about to founder on the rocks at night, is a tour de force.

While Higgins is the protagonist, much of the derring do is assigned to another outsider, Jim Pierce. Powell had seen Roger Livesey at the Old Vic and wanted him for the part, but was vetoed by a studio boss who objected to Livesey’s husky voice. More fool him. Instead, Powell made do with Ian Hunter who, unlike Livesey, was as conventional as they come and seems acutely aware of the role’s limitations. Happily, Livesey would go on to become a key member of Powell and Pressburger’s stock company, beginning with The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943).

***

Powell had the first inklings of an idea about a film set on a Scottish island in 1931, when he spotted a news story about St. Kilda: a Scottish archipelago which was evacuated when the communities there became unsustainable. In the summer of 1936, he finally had the opportunity to break away from quota quickies and make The Edge of the World (1937), which tells the story of a remote Hebridean island and the people who might be forced to leave it behind.

The film was Powell’s most personal work up to that point and perhaps his first masterpiece. It was also a significant leap forward professionally: it garnered the attention of Alexander Korda, who would introduce him to Emeric Pressburger.

Rynox, Hotel Splendide, Red Ensign and The Phantom Light are all interesting as works in progress, time capsules charting the development of an extraordinary artist. Watching them, you catch glimpses of Powell’s visual flair, his appreciation for landscapes and the natural world, his artistic ambition and his sense of humour.

In A Life in Movies, he wrote:

We were told in the thirties, before the war, that the life of a film was about three years. After that, for all that anybody cared, it could be cut into mandolin picks. We believed it, but the fascination of the craft lured us on.

Ten of the 23 films Powell directed between 1931 and 1936 are missing, presumed lost. To be able to see so much of his early work is a gift.

Leave a Reply