Watching Le Million is like getting pulled into the world’s most enthusiastic chorus line: you don’t know all the steps, but you’re having much too much fun to stop.

Watching Le Million is like getting pulled into the world’s most enthusiastic chorus line: you don’t know all the steps, but you’re having much too much fun to stop.

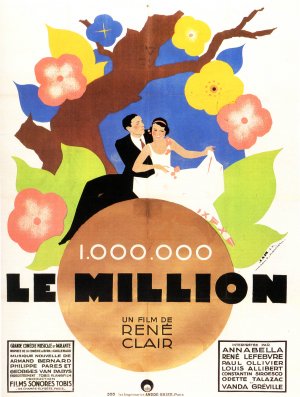

It’s midnight in Paris and there’s a large party going on in a garret—but why? Flashback to earlier in the day, when penniless painter Michel (René Lefèvre) is overjoyed to learn that he has just won a million florins in the Dutch lottery. All he has to do is present his ticket to claim his winnings. Except the ticket is in a jacket he gave to his girlfriend Béatrice (Annabella), who gave it to a charming thief on the run (Paul Ollivier), who sold it to an opera singer (Constantin Siroesco) … Pandemonium ensues.

Le Million is a very funny film. It is also silly, sweet, dazzling and disorienting—a fast-paced musical-farce that’s as densely layered as a wedding cake.

Writer-director René Clair turns Paris into a playground where everything runs on sing-song logic. When Michel is ambushed by the small convention of creditors that have gathered in his apartment building, he decries their “penny-pinching manners” and refuses to pay them. They chase after him, singing “Stop, thief!” and racing up the rickety staircase into a maze of corridors. Above their heads, the police are tottering across rooftops in pursuit of notorious thief Grandpère Tulip. Soon both parties collide and end up chasing the wrong men. Later, opera singer Ambrosio Sopranelli is out shopping when he is forced to prove his identity at gunpoint. (His would-be assailant is hiding behind a mannequin and only the hand holding the gun is visible.) Sopranelli starts singing while the gangster conducts, waving his gun like a baton. The tenor hits a high note which shakes a chandelier from its hinges and the matter is settled.

Indeed much of Le Million’s humour and style stems from its offbeat use of sound. Clair had been making films since 1924 and was sceptical about the advent of sound—early talkies were often static and dialogue-heavy—until he realized that a film’s soundtrack didn’t have to be used realistically. Why have words and images duplicate each other, when you could juxtapose them instead? In Le Million, dialogue is sung more often than it is spoken, some ‘dialogue’ isn’t heard at all, and what you hear isn’t always synchronized with what you see. Clair adapted the script from a play by Georges Berr and Marcel Guillemand, replacing most of their dialogue with songs and adding a chorus of creditors who follow Michel about and comment on the action. In my favourite scene, Béatrice and Michel accidentally wander onstage at an opera house and have to duck behind some fake shrubbery while Sopranelli and a Valkyrie-like diva sing a love duet. Béatrice thinks Michel doesn’t love her anymore; he struggles to convince her otherwise. Their whispered conversation is drowned out by the duet, which coincidentally fits their gestures and expressions perfectly. Later, Clair plays around with the soundtrack to even more startling effect, swapping the score for loud cheers and whistles, and transforming a backstage tussle into a rugby match played by men in tuxedos, with Michel’s jacket as the ball.

In fact, the film is filled with so many technical marvels, the actors’ performances seem secondary by comparison—and that’s probably the idea. Clair sketches people with swift, broad strokes: Béatrice is kind; Michel’s friend Prosper is jealous; the police are crazy; and that’s all we need to know. The only character with any real layers is Michel himself, a cheeky, selfish, womanizing rascal with a heart of gold. René Lefèvre shows him at his brashest (his wounded pride as he nobly refuses to pay his debts) and his most vulnerable (his desperate attempts to win Béatrice back), delivering a standout performance in the process.

One of the most defiantly original films of the early sound era, Le Million is a lyrical masterpiece, full of invention and grace. Quite simply, it’s sublime.

Leave a Reply