Fashion Week recently descended on New York, which got me thinking about women’s clothes in film. The best costumes reveal a character’s tastes and temperament, the way she sees herself and the world sees her, before a single word is spoken.

In The Blue Angel, cabaret singer Lola Lola’s top hat and tights embody Weimar Germany at its most tantalizing. Ballerina Vicky Page, climbing an ancient flight of steps in a teal evening gown, a crown perched on her head, looks like a princess in a fairytale—fitting for a woman about to dance The Red Shoes. Charlotte Vale’s transformation from caterpillar to butterfly in Now, Voyager begins with a crisp black suit and a wide-brimmed hat. But it’s the elegant black gown she wears in defiance of her mother (who prefers drab foulard) that confirms she won’t be forced back into her chrysalis. Clothes make the woman; costumes make the character.

Sabrina (1954) Hubert de Givenchy

Sabrina Fairchild (Audrey Hepburn) goes to Paris to learn to cook, but what she really learns is how to dress. Gone is the schoolmarm-ish sack that made her look like a ragamuffin. In its place is this chic double-breasted wool jacket and matching skirt, with a chiffon turban, perfect for catching the attention of passing playboys (yes, I mean you, David Larrabee). Sabrina marked the beginning of Audrey Hepburn’s long collaboration with Hubert de Givenchy—she personally selected Sabrina’s travel suit from his Spring/Summer 1953 collection. Their influential partnership would also yield Holly Golightly’s iconic little black dress in Breakfast at Tiffany’s and a designer wardrobe that provokes Peter O’Toole to dress Hepburn as a cleaning lady in How to Steal a Million, if only because “it gives Givenchy a night off”.

Paramount Studio’s Edith Head designed Sabrina’s pre-Paris wardrobe and little else, but refused to have Givenchy’s name alongside hers in the credits (standard Hollywood practice at the time was to only list head designers). Notoriously, when Sabrina won it’s only Oscar, for Best Costume Design, Edith Head took all the credit and never acknowledged Givenchy’s contributions. I have great respect for Head’s talent—just look at the next entry in this list—but her treatment of Givenchy has always troubled me.

Rear Window (1954) Edith Head

“Is this the same Lisa Fremont who never wears the same dress twice?”

“Only because it’s expected of her.”

It’s one of the best entrances ever shot: photographer L.B. “Jeff” Jeffries (James Stewart) wakes to see a shadow looming over him; it’s his girlfriend Lisa (Grace Kelly), leaning in for a kiss. At last she pulls away, gliding around the room switching the lamps on and giving Jeff ample time to admire her. A fitted black bodice with a plunging V-neck tapers at the waist, then blooms into layer upon layer of chiffon and tulle in a full white skirt. Tendrils of ferns creep down the skirt from the waist. Immaculate silk evening gloves, a gossamer tulle shawl and a string of pearls complete the ensemble. It’s a wonder the man isn’t breathless.

Lisa Fremont is the sort of woman who can take on any challenge—scaling the Himalayas, breaking into a suspected murderer’s flat, surviving a New York City heat wave without air conditioning—and look fabulous while doing so. Jeff teases her about her wardrobe, but for Lisa, style and self-possession go hand in hand. He’ll catch on eventually.

Casablanca (1942) Orry-Kelly

Ilsa Lund (Ingrid Bergman) is celluloid’s most glamorous refugee. This is what she wears to go shopping. The simple white jumper dress flatters without the least hint of ostentation, while the sun hat which, worn by anyone else, might look like a clumsily inverted saucer, sits perfectly on her head. Ilsa is radiant. She has to be; she’s the centre of a love triangle. She is also the most fashionable member of a very well-dressed ensemble. Rick’s Café Americain is an oasis in the desert, where people can forget about the deprivations of war (or pretend to). Naturally, they all arrive dressed to the nines.

A Place in the Sun (1951) Edith Head

Angela Vicker’s (Elizabeth Taylor) dress means money. The wide white skirt, draped with a layer of tulle dotted with silver spangles, rustles when she walks, like crisp dollar bills. The entire gown is suffused with wealth, the sort of dress worn by a woman who has never wanted for anything. George Eastman (Montgomery Clift) wants things. He doesn’t have money and he wants it. He doesn’t have Angela and he wants her too.

Queen Christina (1933) Adrian

In an era when women wearing trousers was considered scandalous—Katharine Hepburn’s jeans were confiscated from her dressing room at RKO in a doomed effort to stop her wearing them—Greta Garbo played the ultimate tomboy, and got away with it. Christina is her father’s only child and heir and thus a woman raised as a man. She spends most of the film in men’s clothes: tunics and trousers which reveal just how flattering menswear can be on a woman. If that woman is Garbo. Her minimalist black velvet ensemble, with splashes of white at the collar and cuffs, is the 17th century equivalent of business-casual, dignified yet functional. The high starched collar emphasizes her bust, drawing all eyes to her. Rembrandt might have painted her.

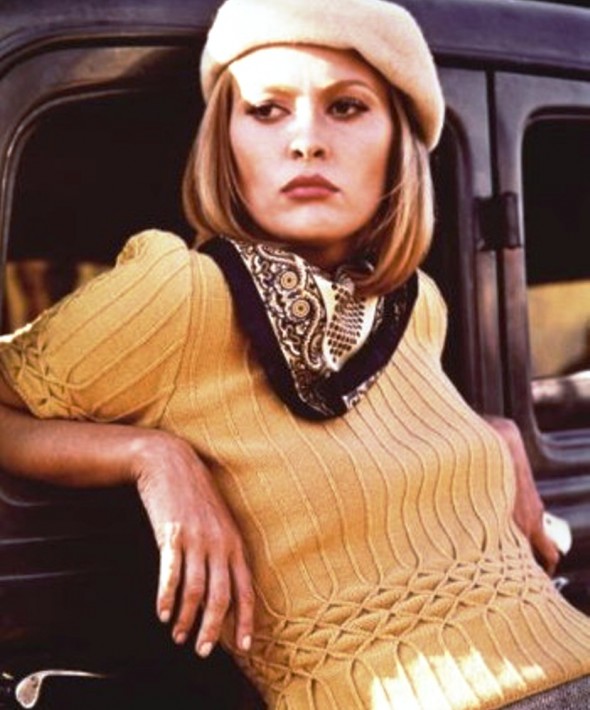

Bonnie and Clyde (1967) Theadora Van Runkle

This here’s Miss Bonnie Parker (Faye Dunaway). She steals the show. The short-sleeved jumper and midi skirt, the scarf tied cowgirl style, the beret: Bonnie Parker is the epitome of outlaw chic. What’s the point of being a notorious bank robber if you don’t dress the part? Bonnie is obsessed with cultivating the image of a glamorous life on the run and her style is as much influenced by the sixties as it is thirties—the Great Depression refracted through a countercultural lens. Her outfits created a sensation; berets flew off haberdashers’ shelves. Bonnie and Clyde was Theadora Van Runkle’s first film as a costume designer and it earned her an Oscar nomination. The look endures, even 50 years on.

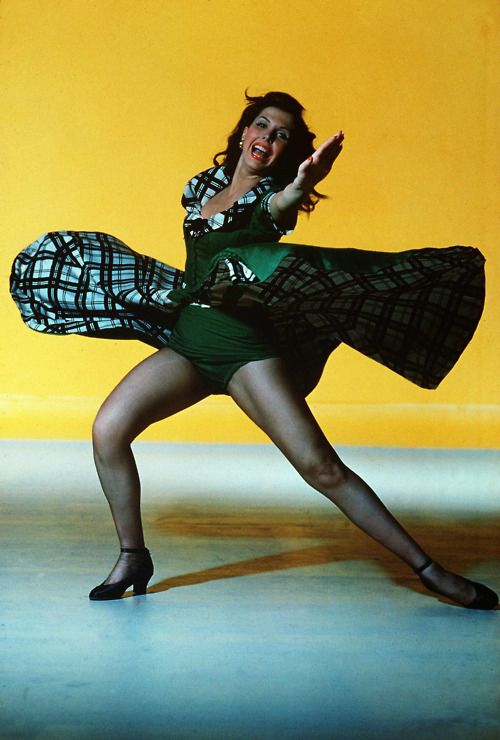

On the Town (1949) Helen Rose

Talk about a ‘swing dress’. Three sailors on a whistle-stop tour of New York drop by the American Museum of Natural History and run into Claire (Ann Miller), a prim anthropologist with a secret hankering for cavemen. Cue song and dance number. Claire’s dress, a verdant green with black-and-white tartan trim, is stylish but otherwise unassuming—until she begins to dance. Then the high-split skirt miraculously unfurls, revealing the beautiful legs of one of the best tap dancers on the MGM lot. Miller whirls like a spinning top.

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) Milo Anderson

As befits a film that gives us the Middle Ages via Burbank, Maid Marian (Olivia de Havilland) is a quintessential fairytale princess. Her wardrobe glows with the full force of three-strip Technicolor and she never wears the same outfit twice. Hennins won’t be in style for another 200 years, yet Marian is still surprisingly fashion forward, wearing a 13th century coif headdress and veil rather than a period-appropriate wimple. Her silver lamé gown, which glistens like a waterfall, isn’t historically accurate either—but I don’t think Robin minds.

Gigi (1958) Cecil Beaton

Gigi’s “little Scotch dress” might be the least self-conscious outfit in Belle Époque Paris. The skirt exaggerates the length of Leslie Caron’s legs, making her look like a gangly colt and the red tartan is exuberant, rather like Gigi herself. It’s the dress of a schoolgirl, which is precisely the way family friend Gaston sees her. But little girls get bigger every day. When Gigi finally decides to wear something more grown up, her new dress sends him headlong into an existential crisis, which he can only resolve through song.

Auntie Mame (1958) Orry-Kelly

Life is a banquet and most poor suckers are starving to death.

Mame Dennis’ (Rosalind Russell) approach to life also applies to her wardrobe. A wealthy socialite with a wide array of interests and boundless enthusiasm, her clothes span multiple influences and styles. One month might find her in a Chinese-inflected black lace trouser suit and sweeping orange jacket. The next in an evening gown so red it seems to vibrate. For flamboyance matched with taste, there’s no one quite like Mame.

Leave a Reply