Inside Daisy Clover has urgent news to impart: Hollywood is full of phoneys. Beneath its sparkling veneer, Tinseltown is a snake pit filled with sycophants and fiends who pay millions for your smile, while also stealing your soul. This revelation isn’t particularly shocking, or much of a revelation, but the film repeats it endlessly and so earnestly it’s almost comical.

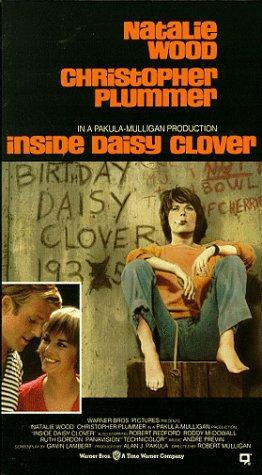

It’s 1936 and teenage Daisy Clover (Natalie Wood) is a scruffy tomboy growing up like a weed in Angel Beach, California. She scrounges a living on the pier, running a stall which sells autographed photos of the stars—she forges the signatures herself—and lives in a shack with her mother (Ruth Gordon), who suffers from dementia. More than anything, Daisy wants to sing. She sends a recording of her voice to studio head Raymond Swan (Christopher Plummer) and is astonished when he not only summons her for an interview, but offers her a contract. Without realising it, Daisy fits an archetype: a combination of orphan and clown that audiences adore. Swan intends to turn her into “America’s Little Valentine” and make millions in the process. Swept up by the Dream Factory, Daisy becomes a star, only to get caught in the gears.

If there’s one thing Hollywood loves more than telling stories about itself, it’s telling stories about its dark side. Based on a novel by Gavin Lambert (who also wrote the screenplay), Inside Daisy Clover takes its place in the queue behind Sunset Boulevard, The Barefoot Contessa, The Bad and the Beautiful, Two Weeks in Another Town, Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, the first two versions of A Star is Born, and countless others—and adds surprisingly little to the litany. The rooms in Swan’s guesthouse are an immaculate, dazzling white because everything about him is whitewash. One of Daisy’s big production numbers is ‘The Circus is a Wacky World’, a perky, candyfloss pink confection in which she appears as a carnival barker and sings: “The circus is a wacky world/ Take it from me/ But it ain’t at all what it’s supposed to be.” The ebullience is aggressive, lest we miss the irony. (Dory Previn wrote the lyrics and André Previn composed the music, along with the rest of the film’s score; Natalie Wood’s voice was dubbed by Jackie Ward, who also sang for her in The Great Race.) As a former child star, Wood probably knew more about Hollywood rot than almost anyone in the cast. But Daisy doesn’t. Despite being a hard-nosed child of the Depression, she remains idealistic enough to believe some scrap of beauty exists in Hollywood. Her disillusionment isn’t surprising; the extent of her credulity is.

At Swan’s Christmas party she meets Wade Lewis (Robert Redford), a matinee idol whose combination of glamour and self-loathing makes him Hollywood in miniature. Daisy wanders into what she thinks is an empty room, only to find him slouching on a bed, resplendent in a tuxedo, a glass of wine dangling rakishly from one hand. Half drunk, he welcomes her to the land of “the Black Swan”, also known as “the Prince of Darkness” and asks, “As one fallen angel to another, would you care to get drunk?” Daisy is instantly smitten. Inside Daisy Clover was only Redford’s second film and he appears in all his early bloom, a golden-haired Adonis with a bewitching smile and enough panache to tug every scene away from Wood.

The rest of the cast is less eye-catching, save for a few standouts. Roddy McDowall, a former child star like Wood, plays Swan’s assistant Baines, an omnipresent yet suspiciously inconspicuous aide who barely speaks, and is as precise and unyielding as a Malacca cane. Ruth Gordon is poignant as Mrs. Clover, whose grip on reality is tenuous but whose love for Daisy is unwavering. Christopher Plummer makes the most of a thinly-veiled Mephistopheles.

Plummer isn’t given much to do, but he is given the film’s best scene. Daisy marries the man of her dreams, only for him to break her heart. She curls up like a child by Swan’s swimming pool and wearily, he tries to comfort her. For the first time Daisy sees him without his armour: his tie and collar are loose, his waistcoat rumpled, his hair tousled. Ruefully, he tells her that if he had warned her, she would have ignored him, dismissing it as his latest attempt to sabotage her happiness. He gently pulls Daisy to her feet, carries her and rocks her in his arms. Plummer is remarkable: charming, affectionate and vulnerable and underneath, coolly manipulative. The whole scene has been a seduction. It’s all so good you wonder if it was lifted from another film entirely.

In its shallowness Inside Daisy Clover closely resembles The Legend of Lylah Clare, another would-be Hollywood exposé that’s largely inert. Released three years after Daisy Clover, Lylah Clare is a Grand Guignol of a disaster by comparison, but the two films share a similar affliction: they are warts-and-all portraits that have nothing new to say. The trouble with Inside Daisy Clover is that there isn’t much inside Daisy after all.

Leave a Reply