There are films I long to see and know I never will: Michael Powell’s Prospero; Orson Welles’ Heart of Darkness; Martin Scorsese’s Gershwin; Max Opühl’s The Duchess of Langeais. Film history is haunted by the spectres of unmade movies, films which for whatever reason—cast reshuffles, vagaries of financing—never saw the light of a projection booth.

Some will only ever exist in the imagination. But for a handful, thankfully, there’s BBC Radio 4’s Unmade Movies, an occasional series which revives unproduced films and adapts them into feature length radio plays. I recently stumbled upon The Blind Man, a might-have-been Alfred Hitchcock thriller, and The Unquenchable Thirst of Dracula, a lost Hammer Horror: two very different plays which made oddly complementary listening.

One of Hitchcock’s many unmade projects—so many Wikipedia has a list—The Blind Man began life as the director’s follow-up to Psycho. Ernest Lehman, the screenwriter behind North by Northwest, wrote a screenplay about a blind pianist (to be played by James Stewart) who receives an eye transplant from a dead man and begins to see again, only to discover that the donor was murdered. The film fell through and Lehman’s script remained unfinished, until the BBC and Mark Gatiss (of The League of Gentlemen and Sherlock fame) stepped in.

The Blind Man plays like an extended episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, with the Master of Suspense himself (an eerily accurate Peter Serafinowicz) narrating the action with his usual droll humour. Hugh Laurie stars as Larry Keating, a famous jazz pianist, blind since birth, who gets an eye transplant and rejoices in his newfound gift of sight. But a dead man’s eyes are thought to record the last thing they saw; the last thing Keating’s saw was a killer.

As MacGuffins go, I can’t think of anything more outré than a pair of eyes. The story is cheerfully preposterous, hopping from a bar in Beverly Hills to a cruise ship bound for Hawaii, with a pit stop at Disneyland, where Keating first encounters Victor Farmer (Nicholas Woodeson)—the man who triggers a vision of a gun being fired in Keating’s face. Listening, I wondered what Hitchcock would have made of a set piece in The Happiest Place on Earth™. Something gleefully sinister, I imagine. And it seems that’s just what Walt Disney feared: one of the reasons the film allegedly collapsed was that Disney had just seen Psycho and barred Hitchcock from filming anywhere near Mickey and the gang.

Laurie does a fine job as Keating, a man with a wisecrack for every occasion who isn’t as invulnerable as he likes to think. Like Roger Thornhill before him, Keating’s impetuousness makes him Fate’s plaything and he never quite gets used to the idea. Lehman and Gatiss’ dialogue (Gatiss also directed) is ridden with innuendos and the cast relishes slinging it around, especially Laurie and Rebecca Front, who plays a sultry femme fatale as far removed from her turn as The Thick of It’s clueless Nicola Murray as the Earth is from Alpha Centauri.

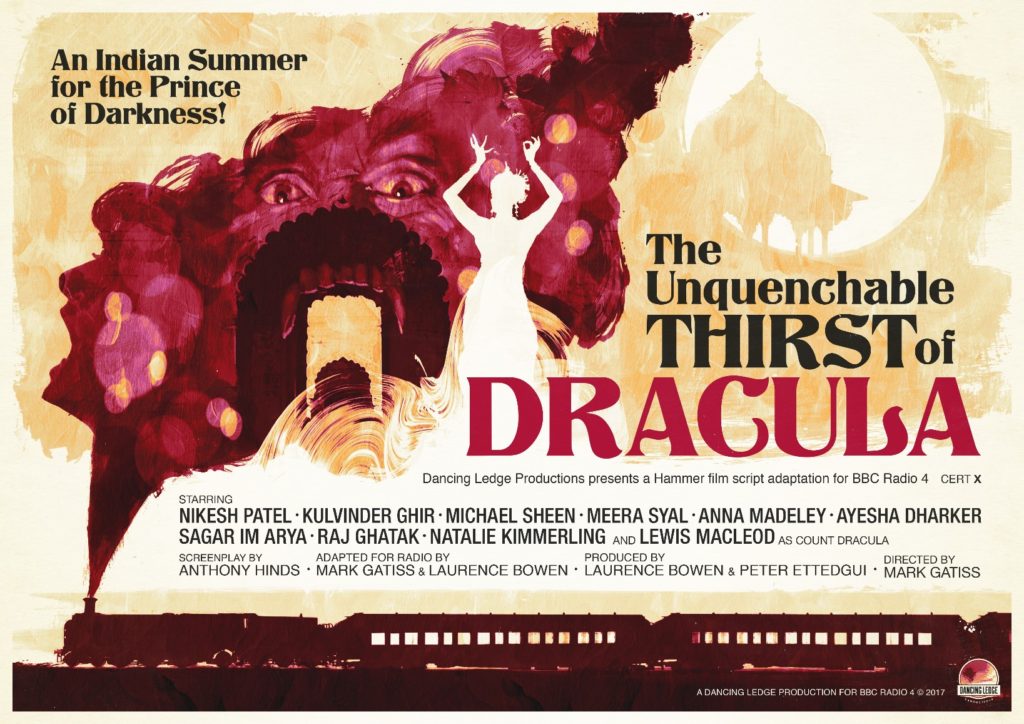

As entertaining as The Blind Man is, I enjoyed The Unquenchable Thirst of Dracula even more. Directed by Gatiss, the play resurrects a script by Hammer stalwart Anthony Hinds, set in India in the 1930s and nearly shot on location there in the ‘70s. (The financing fell apart.) Penny (Anna Madeley), a young Englishwoman, is travelling alone by train, seemingly on a jaunt—in fact she’s looking for her sister, who has mysteriously vanished. In her carriage she meets musician Prem (Nikesh Patel) and his sister Lakshmi (Ayesha Dharker), a dancer, who have been hired for one night by a Maharajah. When they arrive, the siblings find they are to perform for the Maharaja’s guest Count Dracula (Lewis MacLeod) instead. Soon Lakshmi has disappeared and Penny and Prem discover Dracula’s hosts have sanguinary habits of their own.

The play is wonderfully atmospheric, thanks largely to Michael Sheen’s narration. Sheen’s voice, as layered and golden as honeycomb, conjures everything from a cramped train carriage to an opulent palace and the caverns beneath, and bathes it all in gloom.

Hinds’ script is a variation on the standard Hammer story of young people in peril, with a resourceful heroine who resembles Mina Harker and a cast of locals who aren’t stereotypes. Meera Syal is especially good in a dual role as Penny’s kindly hostess and as the malevolent Rani, wife of the Maharajah, high priestess of a bloodthirsty cult and proud enough to repeatedly defy Dracula. I only wish there were more of her, and Sheen.

As his tale draws to a close Hitchcock cheekily says, “Though this entertainment has largely been concerned with the visual realm, we thank you for listening.” You might never be able to see The Blind Man or The Unquenchable Thirst of Dracula, but hearing them makes a fine substitute.

Leave a Reply